Online primary school learning network spreads

The Virtual Learning Network (VLN) has been a developing part of New Zealand’s education system for several years in rural secondary schools and more recently at primary level.

The Virtual Learning Network (VLN) has been a developing part of New Zealand’s education system for several years in rural secondary schools and more recently at primary level.

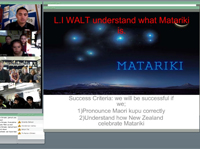

Participation in the VLN involves sharing and delivering classes between clusters across the country. The stated aim of VLN is to support “the concept of classrooms without walls, where students and educators have the flexibility to connect with their classes 24 hours a day, seven days a week.” Now the VLN Primary is beginning to gain momentum.

It is centred on Matapu School, a decile 7, U3 school in South Taranaki. Matapu School is the lead school for VLN Primary through the vision and drive of its principal Rick Whalley, who has for some years worked collaboratively with other rural and remote schools to grow online opportunities for learners.

A total of 35 primary schools have been participating in 2011 and so far this year. In the first semester in 2012, 18 schools were taking part in the 10 classes, all of them teaching languages except for one course in astronomy. In all, there are currently about 200 students from those schools actively participating. This includes an ongoing health project, supervised by senior students from Auckland’s Rosmini College, with three primary schools and 54 students involved. “And we know there are lots of schools connecting with each other under their own steam,” coordinator Rachel Roberts said.

Small beginnings

It is a considerable step up from three schools in Taranaki and Waikato which began it all a few years ago. In 2008, Mr Whalley set up an online collaboration of Spanish and French classes with two other primary schools in Waikato and Taranaki, and approached the Ministry of Education for support. That led to funding for Ms Roberts as part time coordinator in 2010 and 2011. As more schools became involved, the ministry came up with full time funding for her this year, as well as providing the necessary audio conferencing facilities, web conferencing and internet tools. With the advent of ultra-fast Broadband in schools, those involved are looking forward to being able to include video conferencing capability as well. Ongoing funding for sustaining collaboration is still to be secured.

“The VLN is something we’ve been involved with over the years and have been adapting and fine tuning for the needs of primary students,” said Ms Roberts. “While a lot of area schools have younger students and are involved in online learning, they’ve mainly focused their VLN activities on NCEA students, and the younger students haven’t been as involved.”

Courses last from 12 – 15 weeks. Students go online to a web conferencing room, dial in to the audio conference and have a half hour session with students from other schools and their teacher. Real time classes are supplemented through Moodle, an online learning environment with activities, video, games and quizzes that can be accessed at any time, from anywhere.

Ms Roberts says language has been a big driver for VLN Primary because when the curriculum changed in recent years, languages became a separate area of the curriculum and schools were compelled to offer it to their students. “That’s just unrealistic for many New Zealand schools, so VLN Primary has many languages classes.”

She says VLN is all about personalising learning for students, giving them a much wider range of choices than their own school could offer on its own. “The one size fits all model isn’t fair and realistic in today’s world, and so the VLN Primary is really opening up pathways for students to make choices at a younger age.”

The network can also call on expert help when it needs it. “We work with an international language exchange programme, language advisors and the Confucius Institute and can tap into their language assistants. They’ve really got in behind us and support what we’re doing.”

Reciprocity principal

Ms Roberts says the VLN is made possible by schools offering their expertise as a teacher of a subject, and then enrolling their students in the classes VLN offers. “It’s based on the principal of reciprocity and contributing to a shared teaching and learning pool.

“Sometimes, staff at remote rural schools think: ‘We haven’t got the skills to contribute, so how can our students participate?’ The answer is that some might donate resourcing, provide a language assistant, or assist with staffing to a school to help replace the teacher who is delivering VLN there.”

The benefits to the schools are two-fold, she says. “For a lot of our smaller, very remote schools, it’s a great opportunity to have other teachers working with their students, even though it’s at a distance. When there are a dozen kids from three different schools, in a class with a teacher who is from somewhere else, there are not three other teachers sitting in the background. Those kids are interacting independently with their online teacher.

“For participating schools, the payoffs in key competencies are just huge – participating and contributing, managing self and relating to others are all developed in the context of online learning. Teachers can advance their own professional learning, whether it’s in becoming an online learner or teacher themselves or upskilling in any of the classes we offer.

“The students are gaining a wider perspective on learning languages. It gives them an introduction to what’s out there, and when they move on to other primary or secondary schools, we hope they’ll have developed enough love of learning languages to be asking for those subjects.”