Reflecting on the end of National Standards

Professor Martin Thrupp reflects on the end of National Standards, and how researchers and academics contributed to the debates over the standards and to how they are now being thrown out.

I will be referring in places to my recently-published book, with Bob Lingard, Meg Maguire, and David Hursh, entitled The Search for Better Educational Standards: A Cautionary Tale. This book provides a rich account of the rise and enactment of the national standards policy from multiple perspectives. The book also looks at Ngā Whanaketanga Rumaki Māori, the Māori-medium assessment system that accompanied the National Standards.

How not to make policy

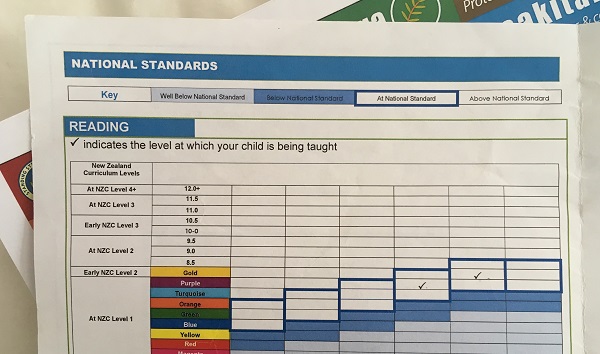

To me, one of the most interesting things about the 2017 general election and National Standardswas the National party’s pre-election announcement that it would be further reinforcing the standards. With the new ‘National Standards Plus’, the reporting of a child’s National Standards data would go online so that parents could track their child’s achievement as they were assessed.

It is tempting to say that National were already in a hole with this policy and should have stopped digging. There had been numerous signs in recent years that that the policy was in trouble (see A Cautionary Tale, chapter 9). Indeed, just the week before National Standards Plus was announced, a feature-length article in the New Zealand Herald had pointed out numerous difficulties with the existing form of national standards.

But the National-led government had become fully invested in the National Standards policy. When it was first announced in 2007, it was National’s big idea for education – the ‘cornerstone’ of its education policy. Over the ten years that followed, the government had dismissed all criticisms. Any late turning back would be a sign of weakness, and instead the National party wanted to plough on with this truly awful project that had already became a world-class example of how not to make education policy.

As shown repeatedly throughout A Cautionary Tale, the national standards were too driven by political rather than educational considerations. As Bob Lingard says in his reflection (A Cautionary Tale, chapter 10):

“The analysis seems to demonstrate that instead of evidence-informed policy what we have here is more a case of policy-based evidence, with the political in the national standards very much overriding research evidence and professional knowledges, to the detriment of the reform”.

The contributions of researchers and academics

Despite the National-led government’s adherence to the national standards, researchers and academics certainly pushed back against the policy. I emphasise this because a recent posting on Diane Ravitch’s popular blog quotes Australian Phil Cullen handing out bouquets and brickbats around the National Standards being thrown out. While I agree with much of what Cullen has to say, the only mention academics get are as “schooliolist academic know-alls”. It is as if we contributed nothing to the campaign against National Standards.

In fact, researchers and academics did a great deal in this space! A particular highlight for me was the 2012 open letter signed by more than 100 education academics against the public release of the National Standards data. But there were countless other instances of academics and researchers opposing the National Standards, either publicly or more behind the scenes. Opinion pieces, articles, TV debates, radio, public meetings, meetings behind closed doors – and all the rest of it. Chapter 8 of A Cautionary Tale, about the politics of research, gives numerous examples.

A number of us also did empirical research that helped to explain how the National Standards were a problem (see A Cautionary Tale, especially chapters 3, 5 and 7). And, of course, New Zealand researchers are part of international networks that are working on the same concerns about high-stakes assessment in other countries (see A Cautionary Tale, especially chapters 2 and 10). Note to Cullen: without doubt, some of the best work in this area is coming from Australian academics.

It is true that some researchers and academics chose to support the National-led government’s national standards policies (A Cautionary Tale, chapter 8). This happened for various reasons that may have included the researchers’ educational views, their political beliefs, the political pressures that were upon them or their organisations, and the advantages that came with supporting the policy. It may have also involved a judgement that it was better to be ‘inside the tent’ and have influence than be on the outside.

But this range of viewpoints among researchers and academics is no different than was seen within the teaching profession and amongst principals, where National Standards also had supporters. Indeed, a central problem that the new Labour-led government will have to grapple with, having removed the National Standards policy, is doing away with the data-driven disposition amongst teachers and principals that grew along with the policy under the previous government.

Looking ahead

Even though most teachers and principals did not like the impact of the National Standards policy, after a decade of its influence New Zealand primary schools are now marinated in the thinking, language, and expectations of the National Standards. This has also had wider impacts, for instance on early childhood education. It will all take a little while to undo.

It’s great, though, that New Zealand primary schools will now be able to spend less time shoring up judgements about children – judgements that have often been pointless or harmful – and instead spend more time making learning relevant and interesting for each child. Removing National Standards should also allow teachers to be less burdened, contributing to making teaching a more attractive career again.